| Raphael's

Masterpieces |

|

Sistine

Madonna |

||

|

Description

picture "Sistine Madonna" |

Altarpiece

of the Virgin Mary |

Mary

is faith incarnate |

||

Back-story

regarding the model |

Travelling

"Madonna" after World War II |

Around

Sistine Madonna |

| |

|

|

| Raphael

Sanzio |

|

|

|

|

| |

The

Sistine Madonna, the iconic Madonna with saints and cherubs that

is the last painting Raphael finished with his own hands before

his premature death, turns 500 years old in year 2014. The Gemaldegalerie

Alte Meister (Old Masters Picture Gallery) in Dresden, proud owner

of the masterpiece, is putting on a major new exhibition to celebrate

the queen centennial. In honor of the special occasion, the painting

has been reframed in what is basically a gilded temple, complete

with modified. |

Among the ancient Greeks the powers of the divine were expressed in the marvellous Venus de Milo;

the Italians, however, brought forth the true Mother of God - the Sistine Madonna» Fyodor Dostoevsky

Sistine Madonna, also called La Madonna di San Sisto, is an oil painting by the Italian artist Raphael. Commissioned in 1512 by Pope Julius II as an altarpiece for the church of San Sisto, Piacenza, it was one of the last Madonnas painted by the artist. Relocated to Dresden from 1754, the well-known painting has been particularly influential in Germany. After World War II, it was relocated to Moscow for a decade before it was returned to Germany. There, it resides as one of the central pieces in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. The painting has been highly praised by many notable critics, and Giorgio Vasari called it a "a truly rare and extraordinary work". Composition. The painting, oil on canvas, measures 265 cm by 196 cm. In the painting the Madonna, holding the Christ Child and flanked by Saint Sixtus and Saint Barbara, stands on clouds before dozens of obscured cherubs, while two distinctive winged cherubs rest on their elbows beneath her. The American travel guide Rick Steves suggests that the unusual worried expression on Mary's face reflects her original placement beside a painting of the Crucifixion.

One of the artist's last Madonnas, the painting was commissioned

by Pope Julius II in 1512 in honor of his late uncle, Pope Sixtus

IV, as an altarpiece for the Benedictine basilica of the Monastery

of San Sisto in Piacenza, a church with which the Rovere family

had a long-standing relationship. It was their requirement that

the image contain both Saint

Sixtus and Saint

Barbara. In 1754, the Sistine Madonna was purchased by the King of Poland; Augustus III and was relocated to Dresden Germany where it regained renewed recognition. It is written that the King of Poland was so moved by the image that he moved his throne to better show the masterpiece to the people. This spiked the German’s passions and created a division of sorts as to whether the piece was in fact art or religion.

After its return to Germany, the painting was restored to display

in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, where guidebooks single

it out in the collection, variously describing it as the "most

famous", the "top", the "showpiece", and

"the collection's highlight". From 26 May to 26 August

2012, the Dresden gallery celebrated the 500th anniversary of the

painting. Back-story regarding the model. She is assumed to be Margherita Luti the daughter of a Roman baker named Francesco... Rafael liked the order. Gnostics of all magical properties especially honored number six (that on the sixth day, according to their teaching, God created Jesus), and Sixtus is just translated as “sixth”. Raphael decided to beat a coincidence. Therefore, compositional pattern, according to the Italian art critic Matteo Fitstsi, encrypts a six: it consists of six pieces, which together form a hexagon. Some believe that Raphael painted clouds in the form of singing angels. In fact, according to the teachings of the Gnostic, they are not angels, and yet unborn souls who dwell in heaven and glorify God. Disclosure of the curtain symbolizes the heavens asunder. Its green color indicates the mercy of God the Father, who sent his son to die for the salvation of men. "The Sistine Madonna" seems to be painted with the illusion of being on a stage. The reason being is that two green curtains are hanging from a curtain rod. These curtains are open and look as though they could be closed at anytime, thus, causing the show to be over. In addition, at the bottom of the picture the cherubs and the miter seem to be resting on the stage floor, and the clouds may in turn be props that the Pope Sixtus II, Holy Barbara, and the Virgin Mary with Christ are standing on. The important colors of the picture are white, red, green and gold and the composition reminds the Cross. |

| |

| THE

SISTINE MADONNA by RAPHAEL SANZIO At the Royal Gallery of Dresden in a small room, alone, is the Sistine Madonna. Its setting is an altar-like structure, upon the base of which a quotation from Vasari identifies the picture and gives us his opinion of it: “For the Black Monks of San Sisto in Piacenza, Raphael painted a picture for the high altar, showing Our Lady with St. Sixtus and St. Barbara — truly a work most excellent and rare.” For nearly four centuries now, Vasari’s opinion has been the verdict of the world. At first glance the picture seems small — the forms are less than life size — and to eyes educated by the Gran’ Duca and the Madonna of the Chair, it appears rather dull in color. Against a background of blue-gray, becoming warmer toward the center of the picture, stands the Virgin. The upper portion of her robe is pink, deepening to red in the shades, over a vest of violet-gray. The lower portion is blue over a skirt of red. The scarf thrown over the shoulder is cream-white. The veil flowing from behind the head is a warm gray. Saint Sixtus is clothed in yellow and orange brocade, lined with red, flung over a soft under- garment of ivory white. Saint Barbara’s sleeves are of yellow and orange changeable silk with blue between the elbow and the shoulder. Her skirt is gray; the mantle is yellow-green. The clouds beneath are of a warm gray. The curtains are dull green, and the green is repeated, with red, in the wings of the cherubs. The larger areas of green, blue, and gray seem to give a dominance to the cooler colors; but presently one discovers that the colors are more subdued and the contrasts softer than usual, and that the whole canvas is suffused with the dim green- golden light of a forest glade in September. In consequence the unity of the whole is much greater in the original than in the reproductions. No one would ever think of being satisfied with a circle cut from the upper part of the picture, except in photograph. Occasionally some critic is pleased to pick flaws in this masterpiece. An American painter, whose works were greater in his own eyes than in the eyes of his contemporaries, used to enjoy saying contemptuously that certain of his acquaintances were in the “Sistine-Madonna stage of art appreciation.” Just what he meant by that he never condescended to explain. The picture is by one whom the Blashfields rank “in the art of composition, the greatest master of the modern world;” by one whom Berenson declares to have been “endowed with a visual imagination which has never been rivaled for range, sweep, and sanity;” by one in whose art, according to Symonds, “thought, passion, and emotion, became living melody.” The Sistine Madonna, “the sublimest lyric of the art of Catholicity,” in the opinion of Lubke, “is and will continue to be the apex of all religious art.” To me it is just that, the apex of all religious art. It rises out of the realm of the particular and temporal into the realm of the universal and eternal. It embodies in visible loveliness the things that abide; it sets forth in inimitable beauty the attitude of the human spirit towards “the Power not ourselves that makes for righteousness.” Sixtus is the embodiment of hope. A man of mature years, seeing clearly the needs of his fellowmen, and knowing well his own limitations, he looks to the Divine for aid. Raphael has represented him kneeling devoutly at the moment when by gesture and voice he is calling the attention of the new-born Saviour of the world to the needs of the vast congregation which the drawing of the curtain has just revealed. His attitude is the attitude of the Psalmist: “Our hope is only in thee.” It is the attitude of Peter: “Help, Lord, or we perish.” Is not that the attitude of thoughtful men everywhere to-day? The reformer looks to Him who said, “All ye are brethren;” the teacher of ethics to Him who gave the golden rule; the student to Him who said, “Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.” The eyes of all who suffer turn involuntarily to the One who invited the weary and heavy laden to come to Him and rest. The hope of mankind for a larger and more abundant life is in God as revealed in the face of Jesus Christ. Saint Barbara is the embodiment of love. In the face of love there is no question, no doubt. Love need not even look above. “My beloved is mine and I am his,” that is enough. But love must look around: “ Behold if God so loved us, we ought also to love one another.” The one immediate possible object of affectionate service for Saint Barbara is this pair of cherubs who seem to have strayed away from the celestial host in the sky and are lost, in abstraction at least. Love would be of some comfort to somebody at once, for Love hears a voice that says, “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” While hope sees the need and looks above for help, love sees the need and looks around for opportunity. Love goes to work, enduring all things, and in women sometimes never failing even when the task is hopeless. Raphael, “the supreme assimilator of all and every material that was fitted to the purposes of art,” did not despise the traditional symbolism of colors. Sixtus loves, hence his robe has a red lining; over this runs an ordered pattern in yellow and orange, the symbols of thoughtful wisdom and benevolence. He wishes the good, as he sees it, for all; he will ask divine aid, but there his activity ends. In Barbara’s robes the yellow and orange, the wisdom and benevolence, flood together indiscriminately, and over this is flung a mantle of green, the symbol of fruitfulness, of that outflowing love that does not rest satisfied without manifesting itself constantly in good deeds. “Not every one that saith unto me, Lord, Lord, shall enter into the kingdom, but he that doeth the will of my Father.” This involves a degree of self-renunciation, hence her skirt is gray. The ideal love is love without weakness; the love that is just, as well as generous, hence Barbara’s arm wears blue, the badge of truth and justice. Mary is faith incarnate. What a face she has! How beautiful! And for delicate suggestion of deep emotion it has but one superior in the whole range of art, namely, that beardless face of the Christ by Leonardo. A blind, unintelligent faith fears nothing, because it knows nothing; an informed faith may have the assurance of certainty, but then it ceases to be faith, having passed over into knowledge. In true faith there lurks forever the question, the uncertainty, the possibility of doubt. That is the secret of the look in Mary’s face. |

| “We

have but faith; we cannot know;

There come moments of bitter experience

“I falter where I firmly trod, |

For the instant of revelation which Raphael has depicted, even Mary, with the living pledge of infinite love in her arms, tastes the bitterness of this cup that the Father presses to the lips of human faith in its every Gethsemane. The prophecy of Simeon is fulfilled, yea, the sword has pierced her own soul also; but her eyes turn not away. Faith would not be faith that could not suffer and endure. Mary’s experience has been the experience of the faithful in every age. Her attitude is typical of the attitude our race has maintained towards the Son of Mary for nineteen hundred years. We question, yet believe; we see the worst, yet trust the best. Men regret the bloody history of Christ’s religion, they neglect His church, they will not have this man to reign over them, and yet from their beds of pain they reach out eager hands to touch His seamless dress for healing, and over their dead bodies they would have repeated the august words, “I am the resurrection and the life.” Mary is the faith of the world, pondering all these things in its heart, pierced through with many sorrows, yet with passionate tenderness still holding the Christ of God in its arms. But

after all, the supreme thing in the picture is the Child. Place

side by side all the faces of the infant Christ ever painted, and

arrange them in the order of physical beauty, of intellectual promise,

of spiritual possibility, or of suggestion of the Divine, and in

every case this face would have to be placed first. Scores of times

Raphael had tried to do the impossible, to paint the face of the

divine-human child; in this, his last attempt, he succeeded.(1)

But why that startled look, that look of painful surprise, that look of fear, in this divine little face? Interpreters of the picture have always said that the curtains were drawn apart that we might have the vision. Undoubtedly that is true; but at the same time, Mary and her Son, coming from the glory unspeakable, are given a sudden vision of mankind. This superhuman child sees before him not only the kneeling congregation to which Sixtus calls his attention, but the vast multitude behind and beyond it. He sees his own future. He sees Rachel weeping for her children, the first to suffer in His name; the thousands enduring the tortures inflicted by pagan Rome; the millions dying in the religious crusades, wars, and massacres of “Christian history” during fifteen hundred years. What wonder that the child, who had been called the bringer of goodwill to men and the Prince of Peace, should be appalled at such a vision, and pierced with sudden fear. “He is wounded by our transgressions, and the chastisement of our peace is upon Him.” (2) As

I sat there, in that quiet room in the Royal Gallery, so much alone,

gazing at this greatest of religious pictures, I realized as never

before the universality of its appeal. Generations of pilgrims from

all countries have bowed before it, in silence, in admiration, and

in tears. Who of them all has not found by bitter experience, like

Sixtus, that his hope is in God alone? Who has not felt with Barbara

that love to God must show itself in service to others? Who has

not memories of supreme moments when the faith of Mary was his,

and he could exclaim with one of old, “Though He slay me,

yet will I trust in Him”? And who has not in some open hour

shared the vision of this divine child, and realized with crushing

certainty that the way to victory is ever the way of the cross?

|

| The

Madonna She is assumed to be Margherita Luti (Italian, ca. 1495-?), the daughter of a Roman baker named Francesco. We believe that Margherita was Raphael's mistress for the last twelve years of his life, from some point in 1508 until his death in 1520. Bear in mind that there isn't a paper trail of, say, a palimony agreement between Raphael and Margherita. Their relationship seems to have been an open secret, though, and there is evidence galore through the artist's paintings that the couple was extremely comfortable with one another. Margherita sat for at least 10 paintings, six of which were Madonna's. However, it is the last painting, La Fornarina (1520), on which the "mistress" claim hangs. In it, she is nude from the waist up (save for a hat), and sports a ribbon around her left upper arm inscribed with Raphael's name. But wait! There's

more! La Fornarina underwent restoration in 2000, and naturally

had a series of x-rays taken before a course of action could be

recommended. Those x-rays revealed that: Whether or

not Margherita was Raphael's mistress, fiance, or secret wife, she

was undeniably beautiful and inspired tender handling of her likeness

in a every painting for which she posed. |

||

| |

Altarpiece of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child In 1512, Raphael was commissioned by Pope Julius II to create an altarpiece of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child for the newly-built Benedictine Monastery of San Sisto in Piacenza. The pontiff required that the painting include Saint Sixtus, in tribute to his uncle Pope Sixtus IV, and Saint Barbara, one of Fourteen Holy Helpers whose powers of intercession are deemed particularly keen. Raphael finished the painting around 1513 or 1514. He died in 1520, and although he designed and worked on other Madonnas and paintings in the six or seven intervening years, his assistants did much of the work. The painting remained enshrined over the altar in the little-known monastery until 1754 when Augustus III, absentee King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, purchased it from the Benedictines for 110,000-120,000 francs. Augustus III, like his father and grandfather before him, was an avid art collector. They created a world-class collection of Old Master paintings with the Sistine Madonna as the jewel in the crown. Legend has it that Augustus moved his throne so the painting could have the best light in the room, but the entire collection had been moved from Dresden Castle to the more spacious Stallgebäude (the Electors’ Stable Building) next door in 1747; thus, either Augustus wanted some alone time in the throne room with the Raphael for a while, or the story is apocryphal. The only Raphael in Germany, the Sistine Madonna was an immediate sensation. Even though Protestant Saxony was uneasy about its very recent Papist extraction and general Catholic imagery, the painting’s embrace of classicism (the Madonna could just as easily be a Juno and the composition follows the ancient principle of the sectio aurea or golden ratio) and its self-aware presentation as a piece of art (see the green curtains in the upper corners and the cherubs down below who rest against a balustrade much like the altar which the altarpiece was created to adorn) made it a favorite with budding Romantics and classicists alike. Goethe wrote a song about it; Wagner made special trips to Dresden just to see it; Alfred Rethel said, “I would not swap for a kingdom the delight I have had from standing before this picture,” and that was before he went insane. As war loomed in 1938, the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister closed up shop and removed its collection to safety in underground storage in Switzerland. Thus the Raphael survived the firebombing of Dresden that so severely damaged the gallery it wasn’t fully reconstructed until 1960. It also survived the Soviet army, which according to its own press had “saved” the precious painting from a flooded out cave. In fact the storage area was climate-controlled and entirely functional; the Soviets simply felt entitled to claim any and all of the enemy’s treasures as payment for all of their own cultural patrimony looted by the Nazis. In 1955, two years after the death of Stalin, the Soviet Union decide to return the Sistine Madonna to Germany as a gesture of goodwill to strengthen relations between the countries. The jewel in the crown went back on display in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. |

World War II and Soviet possession Sistine Madonna was rescued from destruction during the bombing of Dresden in World War II, but the conditions in which it was saved and the subsequent history of the piece are themselves the subject of controversy. The painting was stored, with other works of art, in a tunnel in Saxon Switzerland; when the Red Army encountered them, they took them. The painting was temporarily removed to Pillnitz, from which it was transported in a box on a tented flatcar to Moscow. There, sight of the Madonna brought Soviet leading art official Mikhail Khrapchenko to declare that the Pushkin Museum would now be able to claim a place among the great museums of the world. In 1946, the painting went temporarily on restricted exhibition in the Pushkin, along with some of the other treasures the Soviets had retrieved. But in 1955, after the death of Joseph Stalin, the Soviets decided to return the art to Germany, "for the purpose of strengthening and furthering the progress of friendship between the Soviet and German peoples." There followed some international controversy, with press around the world stating that the Dresden art collection had been damaged in Soviet storage. Soviets countered that they had in fact saved the pieces. The tunnel in which the art was stored in Saxon Switzerland was climate controlled, but according to a Soviet military spokesperson, the power had failed when the collection was discovered and the pieces were exposed to the humid conditions of the underground. Stories of the horrid conditions from which the Sistine Madonna had been saved began to circulate. But, as reported by ARTnews in 1991, Russian art historian Andrei Chegodaev, who had been sent by the Soviets to Germany in 1945 to review the art, denied it: It was the most insolent, bold-faced lie.... In some gloomy, dark cave, two (actually four) soldiers, knee-deep in water, are carrying the Sistine Madonna upright, slung on cloths, very easily, barely using two fingers. But it couldn’t have been lifted like this even by a dozen healthy fellows... because it was framed.... Everything connected with this imaginary rescue is simply a lie. ARTnews also indicated that the commander of the brigade that retrieved the Madonna also described the stories as "a lie", in a letter to Literaturnaya Gazeta published in the 1950s, indicating that "in reality, the ‘Sistine Madonna,’ like some other pictures, ...was in a dry tunnel, where there were various instruments that monitored humidity, temperature, etc." But, whether true or not, the stories had found foothold in public imagination and have been recorded as fact in a number of books. After its return to Germany, the painting was restored to display in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, where guidebooks single it out in the collection, variously describing it as the "most famous", the "top", the "showpiece", and "the collection's highlight". From 26 May to 26 August 2012, the Dresden gallery celebrated the 500th anniversary of the painting. Wikipedia |

|

Gemaldegalerie

Alte Meister Dresden The

renowned Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister gallery in Dresden, one of

the best art museums in Europe, houses one of the finest collections

of Old Master paintings in the world. The museum has an extensive

collection of Italian Renaissance art including works by Titian

(1488–1576), Raphael (1483–1520), Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506),

Antonio da Correggio (1489–1534), Parmigianino (1503–40)

and Tintoretto (1518–94). |

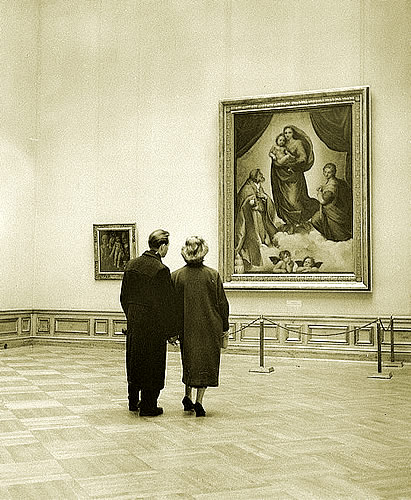

Some step back to get a better look, and step forward again. Others imitate the angels’ poses.

Perhaps a few even relate to the words of German author Thomas Mann:

“My greatest experience, as far as paintings go, continues to be the Sistine Madonna in Dresden.”

Visitors before the "Sistine Madonna" by Raphael Dresden. Zwinger, Semper Gallery, Alte Meister Foto: Peter, Richard sen., 1964/1977 Deutsche Fotothek |

|

The center lancet depicts the Virgin Mary, in a window that copies the famous Sistine Madonna (1508, Dresden) by the High Renaissance artist Raphael. As much as he admired the Pre-Raphaelites, La Farge never shared their disdain for the sensuality and idealized naturalism of the Renaissance artist Raphael. Indeed, he was very sympathetic to the Italian artist’s reconciliation of earthly beauty and spiritual perfection, which he attributed to Raphael’s synthesis of paganism and Christianity.[4] He marveled that he found prints of Raphael’s works “even in Cannibal Land” in the South Seas.[5] La Farge sought to revive the art of stained glass while building on the traditional ideals of art to bring about an American Renaissance. John

La Farge (March 31, 1835 – November 14, 1910) |

Hans Gyenis (1873-after 1926) Fachsimpelei vor der Sixtinischen Madonna Tuschfederzeichnung 1908.51 x 39,5 cm. Signiert mit Datumsstempel 13. Jan. 1908 |

| Sistine

Madonna on the stamps |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References |

|

| • Raphael's Sistine Madonna Paperback by J. I. Mombert, Kiefer Press (September 14, 2011) |

| Copyright

© 2004 abc-people.com Design and conception BeStudio © 2014-2023 |

Friedrich

Nietzsche called her "the vision of the future wife."

Johann Wolfgang Goethe revered her as the "queen of all mankind."

Thomas Mann praised her as "my greatest experience in the art

of painting."

Friedrich

Nietzsche called her "the vision of the future wife."

Johann Wolfgang Goethe revered her as the "queen of all mankind."

Thomas Mann praised her as "my greatest experience in the art

of painting."