|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

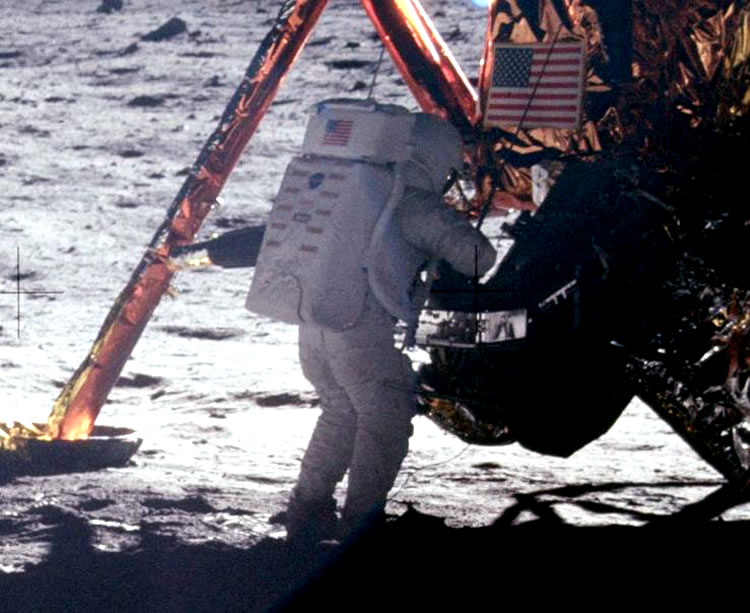

July 20, 1969: One Giant Leap For Mankind July 1969. It's a little over eight years since the flights of Gagarin and Shepard, followed quickly by President Kennedy's challenge to put a man on the moon before the decade is out. It is only seven months since NASA's made a bold decision to send Apollo 8 all the way to the moon on the first manned flight of the massive Saturn V rocket. Now, on the morning of July 16, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins sit atop another Saturn V at Launch Complex 39A at the Kennedy Space Center. The three-stage 363-foot rocket will use its 7.5 million pounds of thrust to propel them into space and into history. At 9:32 a.m. EDT, the engines fire and Apollo 11 clears the tower. About 12 minutes later, the crew is in Earth orbit. After one and a half orbits, Apollo 11 gets a "go" for what mission controllers call "Translunar Injection" - in other words, it's time to head for the moon. Three days later the crew is in lunar orbit. A day after that, Armstrong and Aldrin climb into the lunar module Eagle and begin the descent, while Collins orbits in the command module Columbia. Collins later writes that Eagle is "the weirdest looking contraption I have ever seen in the sky," but it will prove its worth. When it comes time to set Eagle down in the Sea of Tranquility, Armstrong improvises, manually piloting the ship past an area littered with boulders. During the final seconds of descent, Eagle's computer is sounding alarms. It turns out to be a simple case of the computer trying to do too many things at once, but as Aldrin will later point out, "unfortunately it came up when we did not want to be trying to solve these particular problems." When the lunar module lands at 4:18 p.m EDT, only 30 seconds of fuel remain. Armstrong radios "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed." Mission control erupts in celebration as the tension breaks, and a controller tells the crew "You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue, we're breathing again." Armstrong will later confirm that landing was his biggest concern, saying "the unknowns were rampant," and "there were just a thousand things to worry about." At 10:56 p.m. EDT Armstrong is ready to plant the first human foot on another world. With more than half a billion people watching on television, he climbs down the ladder and proclaims: "That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind." Aldrin joins him shortly, and offers a simple but powerful description of the lunar surface: "magnificent desolation." They explore the surface for two and a half hours, collecting samples and taking photographs. They leave behind an American flag, a patch honoring the fallen Apollo 1 crew, and a plaque on one of Eagle's legs. It reads, "Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon. July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind." Armstrong and Aldrin blast off and dock with Collins in Columbia. Collins later says that "for the first time," he "really felt that we were going to carry this thing off." The crew splashes down off Hawaii on July 24. Kennedy's challenge has been met. Men from Earth have walked on the moon and returned safely home. |

In an interview years later, Armstrong praises the "hundreds of thousands" of people behind the project. "Every guy that's setting up the tests, cranking the torque wrench, and so on, is saying, man or woman, 'If anything goes wrong here, it's not going to be my fault.'" In a post-flight press conference, Armstrong calls the flight "a beginning of a new age," while Collins talks about future journeys to Mars. Over

the next three and a half years, 10 astronauts will follow in their

footsteps. Gene Cernan, commander of the last Apollo mission leaves

the lunar surface with these words: "We leave as we came and,

God willing, as we shall return, with peace, and hope for all mankind." |

By

the President of the United States Of America Since the historic flight of Apollo 11, American astronauts have extended man's exploration of the moon to the Ocean of Storms with Apollo 12 and the hills of Fra Mauro with Apollo 14, with rich scientific return. Next week, Apollo 15 is scheduled to head for another different region of the moon to explore the base of the 12,000-foot Apennine Mountains and the rim of the 1,300 foot canyon-like Hadley Rille. Thus, two years after the first landing on the moon, other brave men are following in the footsteps of Armstrong and Aldrin to explore the unknown and advance scientific knowledge for the benefit of all mankind. To commemorate the anniversary of the first moon walk on July 20, 1969, and to accord recognition to the many achievements of the national space program, the Congress, by Senate Joint Resolution 101, has requested that the President issue a proclamation designating July 20, 1971, as National Moon Walk Day. Now, Therefore, I, Richard Nixon, President of the United States of America, do hereby designate July 20, 1971, as National Moon Walk Day. I urge all Americans, and interested groups and organizations, to observe this day with appropriate ceremonies, activities, and programs designed to show their pride in this great national achievement. In

Witness Whereof, I have hereunto set my hand this twentieth day

of July, in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred and seventy-one,

and of the Independence of the United States of America the one

hundred and ninety-sixth. |

Neil Armstrong 1st person to walk on the Moon |

NEIL ARMSTRONG, 1ST PERSON TO WALK ON THE MOON, DIES AT 82 Neil Armstrong, the man whose name became synonymous with the word "astronaut" when he was crowned a national hero as the first human ever to set foot on the moon on July 20, 1969, died Saturday in the Cincinnati area. He was 82. Born

in Wapakoneta, Ohio, on Aug. 5, 1930, Armstrong took an interest

in flight at an early age, and at 17 attended Purdue University

to study aerospace engineering. In 1949, he joined the United States

Navy, where he qualified as a Naval Aviator. He joined Air Squadron

51 and saw action in the Korean War. |

Then came Apollo 11. Armstrong was selected to command the mission in December of 1968. In the spring of 1969, NASA administrators decided that, as commander, he would also be the first of the crew to set foot on the lunar surface. Today, the mission is most remembered for Armstrong's first step off the lunar module ladder and his famous words: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind" (though he maintained the quote should read "a man"). But for Armstrong, the most memorable part of the mission would always be the landing. While command module pilot Michael Collins orbited above, Armstrong and crewmate Buzz Aldrin began the nine-mile descent to the Eagle's designated landing area, but the overloaded onboard computer couldn't keep up with all the commands it was intended to follow, and the craft overshot its mark. With craters and boulders all around, Armstrong was forced to manually find a place to set the module safely down. He later called the final 500 feet of the descent "by far the most difficult and challenging part" of the mission, and even said he enjoyed piloting more than he did walking on the moon. "Pilots

take no particular joy in walking," he said. "Pilots like

flying." "We were not naive, but we could not have guessed what the volume and intensity of public interest would turn out to be," he said. Apollo 11 would be Armstrong's final spaceflight. He left NASA in 1971 and taught aerospace engineering at the University of Cincinnati until 1979. He was also a successful investor and businessman throughout his post-astronaut life, but eventually returned to NASA to lend a hand in a time of crisis, serving as vice-chairman of the commission investigating the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986. Though he left space behind at the age of 38, Armstrong spent the rest of his life advocating for the continued prominence of American spaceflight. Just last year, he appeared before the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology to lament the state of NASA and call for greater support of the agency. "For

a country that has invested so much for so long to achieve a leadership

position in space exploration and exploitation, this condition is

viewed by many as lamentably embarrassing and unacceptable,"

he said. "A lead, however earnestly and expensively won, once

lost, is nearly impossible to regain." On behalf of the Aldrin family we extend our deepest condolences to Carol & the entire Armstrong family on Neil's passing-He will be missed August

25, 2012 (Via Washington Post) |

NASA HAS BEEN PREEMPTIVELY SUED TO PROTECT NEIL ARMSTRONG-GIFTED MOON DUST Astronaut Neil Armstrong may be back in the news for an upcoming biopic, but another piece of his legacy is stirring up controversy in real life. Well, pieces of his legacy. According

to the The Washington Post, a lawsuit has been filed against NASA

by Laura Murray Cicco in order to keep ownership of a vial of moon

dust allegedly gifted to her as a child by family friend Armstrong.

NASA

hasn’t yet made moves to seize the vial, but the agency does

have a history of taking lunar mementos — all according to

policy in its Lunar Allocations Handbook. “Lunar samples are

the property of the United States Government,” the handbook

states, “and it is NASA’s policy that lunar sample materials

will be used only for authorized purposes. It is therefore essential

that rigorous accountability and security procedures be followed

by all persons who have access to lunar materials.” As

for the dust itself? Maybe moon, maybe not. The results have thus

far been inconclusive, reports the Post. That said, it’s hard

to say the dust didn't come from the moon, which means the mysterious

vial is being held in an undisclosed and safe location until the

question of legal ownership is settled. NASA has yet to respond

as of this posting, but the lawsuit was recently served and, as

McHugh told Gizmodo, the space agency has 60 days to respond. |

|

||||||

|

||||||